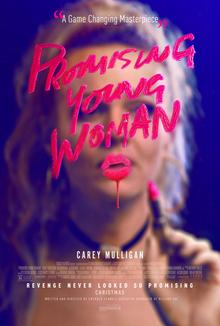

“Promising Young Woman”

Content Warning: This review covers issues of sexual assault, violence against women and suicide as well as uses potentially triggering language. If these themes might be difficult for you, it is totally fine to skip this review for prioritising your well-being.

One thing that everyone can certainly agree upon is that Promising Young Woman (2020) forces its audience to develop their own opinion about the presented story. Its unapologetic and brutal representation of all the ways society legitimises and excuses rape culture and male violence admittedly was hard to watch at times.

But before I go into my opinions about the film, here is a short summary. Promising Young Woman is written and directed by Emerald Fennell and follows Cassie Thomas (played by Carrey Mulligan) as she has put her own life on halt in order to avenge her dead friend Nina who was raped and who never received any form of justice ending with Cassie fulfilling her revenge by getting Nina’s rapist arrested for having murdered herself a day earlier.

Most notably, this film is brutally honest, which at times is its biggest strength and its worst failure. But before I get into the negatives, I want to highlight how the film positively discusses rape culture.

First, the film not only has awesome performances throughout, but its witty and poignant dialogue and chapter structure truly elevates this ‘rape-revenge trope’ into a formally subversive story. The title itself, Promising Young Woman, encapsulates the film’s cruel honesty, because it sets up this optimistic tone of young women being able to achieve something for themselves nowadays since feminists seemingly destroyed patriarchy in 1970s (I wish), only to brutally expose how young women are not only structurally and physically traumatized, but also how they are fundamentally not seen as human beings with interests but merely viewed as being whole once they become someone’s girlfriend. Maybe this is something that not every viewer will be able to relate to, but for me, the continuous microaggressions or overt harassment that the protagonist has to endure (either from her parents, her boyfriend, authority figures or random male strangers on the street) truly made me feel connected to Cassie and her rage whilst watching the film.

The cinematography only emphasises this haunting representation of what it means to exist as a (white, cis-gender) woman in the West. The saturated colour palette contrasted with the unsettling camera movements and techniques such as using fisheye lens or Dutch angles in key moments in the protagonist’s life and choices smartly subvert the overdone masculine vigilante genre as well as the overly objectified representations of women. In doing so, it visually reiterates how life in a contemporary patriarchal system is designed to look fun and colourful and how on the surface these traumatic violations that destroy women’s lives done by men are invisible for people who prefer to stay ignorant and who are not willing to listen to victims and hear their side of the story.

The cast’s wardrobe also has been carefully designed to reiterate the stickiness of old heteronormative patriarchal views concerning women’s spaces in society. Once Cassie starts dating Ryan aka ‘the nice guy’, they both wear characteristically blue and pink clothing, and when they are eating dinner with Cassie’s parents, the pair visually wears the exact same clothes than her parents, highlighting how patriarchal values and norms are reproduced in the younger generation and how both men are essentially patriarchs because they do not respect or care about the ideas, feelings or achievements of their female partners but simply like the comfort and care work that they provide for them.

Probably most productively, using clothing, the film also drives home the point how this vigilante genre is not only masculine (when she is on ‘the hunt’ or when she confronts key figures involved in covering up the rape of Nina, she is constantly wearing blue), but literally ends the movie with her dressing up as THE male fantasy version of her ideal profession, namely sexy nurse, walking to the bachelor’s party using a rendition of Britney Spears’s ‘TOXIC’. The multiple meanings of using Spears’s music, who arguably has suffered the exact forms of brutalisation by abelist patriarchy that the film critiques, is beautiful to watch as a viewer and truly drives home the point that this rape-revenge trope is toxic masculine in itself and heavily caught up in a narcissistic obsession with justice.

The messaging of toxicity with which the film introduces the quasi finale of the film therefore can be read as a witty criticism towards an entire trope concerning rape, since rather than empowering the woman that seeks revenge at the end of the film, it denies this postfeminist narrative out right and painfully lets its viewers know that in this world, the female vigilante has to give up her ‘promising’ life ahead of her and can only achieve justice post mortem. It also shows that the only people who got emotionally traumatised in Cassie’s revenge plot (up until the film’s very ending), where other women, who protected Nina’s rapist through complicity in the past, exposing how these individualistic (masculine) revenge stories will not be the answer for destroying the patriarchy and empowering all women. Rather, the film makes it clear that Cassie taking up the power position of a traditionally white male protagonist is not feminism per se because in the process of getting revenge she is actively and predominantly harming other women.

Cassie’s vigilantism causing other women harm also segues nicely into the more confounding aspects of this film. Specifically, I want to touch upon three issues that came to mind.

The first issue I had concerns the ignorant white feminist politics that this film oozes. Throughout Promising Young Woman, not only is there a physical absence of diverse female representation and the intersectional experience of rape culture, but the only woman of colour, Gail (played by Laverene Cox), reiterates the racist trope of sassy black friend, whose only task is to enable the white protagonist to go on their journey whilst not having any personality, problems, feelings, or issues of her own. On this note, the film also makes no attempt to display how rape culture functions in relation to other oppressive power structures, such as white supremacy or heteronormativity/heterosexuality, amongst others and consequently deliberately ignores several groups such as women of colour, LGBTQIA+ community as well as men (who contrary to popular belief also experience rape) out of the calculation. Hence, although I appreciate several points this film has to say about rape culture, it seems that it has chosen to reiterate common beliefs about rape rather than to complexify the issue.

The other problem I had whilst watching the film was its harmful portrayal of female friendships or better, the lack thereof. Although the film critically thematises the obsessive tendencies that Cassie has for Nina and her subsequent desire to avenge her, Cassie’s adoption of a masculine vigilante behaviour also leaves her in this weird space where the only female friend she has is Gail who literally is her boss. Every other woman in the film is shown as being either part of the problem of rape culture or not wanting Cassie’s attention anymore, such as Nina’s mum or arguably Cassie’s mum as well. This lack of portraying women as a source of sisterhood and instead preferring to portray them as obstacles or double agents of ‘the patriarchy’ sometimes bored me a bit because it plays into this direct harmful strategy that historically has been used to pit women against each other and present them as a threat to one another. I am totally aware of the fact that this might be the film’s very message, namely that white women adopting white male behaviours and recklessness to avenge a dead loved one does not forge the true sisterhood that is needed to overthrow the entire harmful system, I nevertheless felt a bit let down by the Ur-cliché of female competition/threat playing out even if it is meant as subversion.

Apart from that, I also was truly confused about this film’s intended audience whilst watching it. Since Promising Young Woman deliberately exposes the brutal traumatising experiences, harassment and microaggressions that women have to endure on a daily basis inflicted by either close loved ones or random strangers without giving the viewer the satisfaction of seeing any helping sisterhood or fruitful act of ‘revenge’ that equally puts these horrible men into the position of the powerless, throughout my viewing experience I honestly just became retraumatized to some extent and enormously saddened by the film’s brutal and hopeless conclusion. And although I understand the film’s feminist project on a theoretical level, namely that it wants to actively show that individual revenge quests will never be the answer for ending systemic oppression, I left the film feeling sort of disempowered and beaten down. On the contrary, if I as a woman was not the ‘intended audience’ for this movie, but rather conventional ‘dude bros’ who often are the very problem that the film addresses, then this film unfortunately does not offer any scripts to these men of how to recognise their own harmful behaviours or leave them with scripts of how they can call this sort of behaviour out in their friends and prevent these life-altering and life-ending violations inflicted upon women in the future.

Therefore, if this film neither addresses intersectional perspectives, be it based on ethnicity, sexuality, or gender identity, and if it only portrays female suffering without leaving any room for sparking hope, then I seriously have to question this film’s ethics as well as supposed ‘feminist’ narrative.

Isn’t the project of feminism to empower ALL women and shouldn’t it celebrate and make visible diverse representations of womanhood in the 21st century? Is constantly showing another traumatising and (white) portrayal of rape culture productive for inspiring change? Or shouldn’t feminist storytelling always counterbalance exposing and visualising trauma with hopeful and joyful celebrations of resisting patriarchy? Shouldn’t art that takes its politics seriously in general try to point to the deep societal shortcomings and then try to evoke change, to move its audience into action, to provide them with tools that can actually dismantle the master’s house?

So, after all this is said and without wanting to be too critical here: I can see Promising Young Woman as a visually and narratively intriguing yet tragic human story that certainly offers an interesting conversation starter to talk about.

And despite my criticisms, I really do think Promising Young Woman is a masterclass (I hate this word) in effective and creative storytelling, in creating a fresh and female visual language for the 21st century, in portraying hauntingly relatable scenarios and dialogues that invoke a deep feeling of discomfort that I could feel through the screen, whilst having strong white feminist undertones that ignore any nuanced discussion of how white women have a history of being complicit in weaponizing their ‘innocence’ against especially black men, of how rape culture is a monster that appears in many shapes and sizes that are all affected by one’s class, one’s sexuality or one’s ethnicity amongst others, which ultimately left me confused as to who this film is exactly for and how this artwork can inspire change.